It’s been awhile.

The internet got shut off. Life got complicated. Enderender maintenance became less of a priority.

Sine last posting, I traveled by thumb from Portland, Oregon to Los Angeles California. I came back to New Orleans afterwards and things were bad. Then I left America at the start of last year, went travelling in the Middle East. I returned to New Orleans, this time in late spring. Now I work in a public library.

Perfect. That’s the explanation for the my nearly 18-month absence. Now, to readjust focus…

A list of recent reading material, in no particular order:

Common Ground In A Liquid City by Matt Hern

Ideas for sustainable urban futures specifically focused on arguments for density, localization, and city planning as a collective, participatory activity. The premise for this collection of essays centers around the comparison of various locales (New York, Las Vegas, Istanbul, Diyarbakir–to name a few) to the author’s own, Vancouver. The result is a civic-minded sampling of the successes and failures of different cities, with special attention paid to the possibilities of the places being analyzed.

Common Ground has a lot to with basic considerations of public space. A lot of the themes throughout the book suggest that in order to transform our cities–whether it be through redesign, repurposing, or rehabilitation–we need to first change the way we think about them.

Makes sense. Hern’s approach to the shaping of cities is informal, organic, and spirited. He’s into bikes, potlucks, and as much shared space as possible. Corporate interest and privatization don’t make for the kind of city he’s trying to envision in this book. Essentially, he’s calling for cities to be built from the ground up, to develop character on their own, rather than be assigned one by aggressive development firms and government officials.

The writing is consistently approachable, although he could probably stand to put a little more effort into the visuals accompanying his next book. It wouldn’t be unfair at times to categorize Hern as “idealistic”. Of course, imagining the type of place we want to live and be a part of is a lot easier than actually implementing the changes necessary to make that place a reality. His best argument is for densification, building fecund urban centers with lots of resources and preserving the rural areas in the process.

I’d probably be pulling quotes from it if I didn’t already lend it out, recommending it to a friend as definitely worth reading.

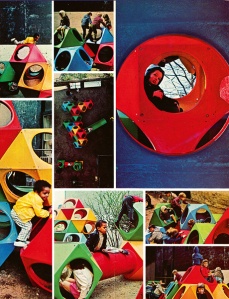

Reimagining Recreation by James Trainor

I developed a weird fascination with playscapes awhile back. This article is about the trials of New York City playground development, the radical urban playground designers of the 60’s, and Robert Moses.

In my reading, I was dragged back to the age of six-years old, running around on what would now be most certainly condemned as a totally unsafe playground at The Hansen Elementary School in the suburbs of Massachusetts. It’s gone now, replaced by a generic, prepackaged play environment. It was made mostly out of thick lumber and old tires. There was a pyramid you could crawl on top of and around and inside, made completely out of conjoined automobile tires! And it was on the huge monster-truck tires, half-buried in the sand, with an 8-foot gap in between them traversable through a rope swing, where I split open my forehead. Lots of crying, some stress for my father, and a few stitches.

I look back upon that place as magical, maybe even more so because of my painful experience.

Lady Allen of Hurtwood, “a British landscape designer and fierce child welfare activist” and one of the major influences of Richard Dattner, a radical playscape designer, was known for her “…unsettling dictum, ‘Better a broken bone than a broken spirit’.”

Reimageining Recreation does a good job of positioning these designers amongst fine artists and, especially, land artists. It’s seems totally reasonable to talk about playgrounds and the Spiral Jetty or Roden’s Crater in relation to one another, conceptually juxtaposing these spatial interventions.

Regarding the radical playscapes of NYC circa 1960:

The playscapes were the first in New York to be designed by architects—idealistic, savvy, and ambitious young designers with their own tots in tow, steeped in New Left politics, versed in current social theories and child psychology, and at home in downtown art circles. (Friedberg was a lifelong friend of artist Jackie Ferrara, whose feminist take on post-minimalism featured wooden staircases, ramps, and stacked pyramids that almost invited the viewer to start climbing on them.) Unbeknownst to most, Dattner and Friedberg embodied a small but important vanguard working in parallel and often anticipating the environmentally engaged work of Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt, Robert Morris, Sol LeWitt, and others.

Operation Delirium by Raffi Khatchadourian

Totally scary, fascinating article about an army doctor conducting drug experiments on young soldiers during the cold war. This expose calls into question the ethics of the US Government feeding young men illicit substances in the interest of developing psychological weapons. Centered around James Ketchum, one of the leading doctors at Edgewood, the article is a collection of horrors and cold military rationale:

In 1949, L. Wilson Greene, Edge wood’s scientific director, typed up a classified report, “Psychochemical Warfare: A New Concept of War,” that called for a search for compounds that would create the same debilitating mental side effects as nerve gas, but without the lethality. “Throughout recorded history, wars have been characterized by death, human misery, and the destruction of property; each major conflict being more catastrophic than the one preceding it,” Greene argued. “I am convinced that it is possible, by means of the techniques of psychochemical warfare, to conquer an enemy without the wholesale killing of his people or the mass destruction of his property.

Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City by Guy Delisle

Guy Delisle documented, in comicbook form, his year spent in Jerusalem. His partner worked for Doctors Without Borders, spending much of her time in Gaza, while Delisle looked after his two young children and explored his surroundings. What came out of this is a very honest account of Delisle’s personal experiences in a place of conflict.

I think the initial naiveté of the author is actually one of the strengths of the work. From the beginning, he seems routinely surprised at the conditions produced from the tensions between Israel and Palestine. He’s not visiting Israel for religious or historical reasons, nor is he visiting Palestine in the interest of solidarity or politics. Instead, it seems more like he just ended up there, the caretaker for the kids while his wife was at work. For this reason, Delisle’s perspective is valuable. Simple and straight-forward.

It’s a good counterweight to reading Joe Sacco….but if you’re going to only read one, definitely choose Sacco.

The Time Machine by H.G. Wells

I’ll spare you from my own unabashed adoration of the father of modern science fiction and just leave you with a crude synopsis: A scientist travels way far into the future. The leisure class has turned into supple, dim-witted imps, the working class into subterranean savages. The future looks bleak.

‘For the first time I began to realize an odd consequence of the social effort in which we are at present engaged. And yet, come to think, it is a logical consequence enough. Strength is the outcome of need; security sets a premium on feebleness. The work of ameliorating the conditions of life–the true civilizing process that make life more and more secure–had gone steadily on to a climax. One triumph of a united humanity over Nature had followed another. Things that are now mere dreams had become projects deliberately put in hand and carried forward. And the harvest was what I saw!’

Home at the End of Time: Robert Vicino Built an Underground City Where You Can Ride out the Apocalypse by Austin Considine and You’re (Probabaly) Not Invited: End Times Living with the Doomsday 1 Percent by Jake Hanrahan

Both these articles came from the same place (Motherboard), around the same time (the Mayan Apocalypse), and deal with the same content (doomsday bunkers) so I grouped them together.

Remember 2012? Like last year, when that thing didn’t happen? Well, at the very least, it propelled “the end of the world” into the mainstream for awhile, which was exciting and then, quickly, tired and annoying.

When reading about these survival bunkers, I can’t help but think of that old Don Johnson movie A Boy and His Dog. I’m specifically thinking about the post-apocalyptic, subterranean community that kidnaps the young Don Johnson for his sperm. In this underground society created in the aftermath of nuclear disaster, it’s all hyper-Americana and inbreeding, weird violence and verbal instructions for apple pie blasting out of speakers. Not necessarily a future worth sticking around for.

What Robert Vicino’s bunker company Vivos offers is the economic version of the doomsday domicile. The going rate for a spot in one of his bunkers is $50,000 per adult, $35,000 for children. Vicino said reassuringly, “What Vivos is, is a modern-day fortress or citadel, where our members are safe and secure, with all the supplies they need to ride it out. And we can defend the facilities. So if the rest of the world’s gone crazy, our people will at least be in a safe haven,”

Sounds fun. And according to the Vivos website, this mass hysteria, necessitating a flee from collapse into the underground, could be a result of any number of forces including, but not limited to, bio war, anarchy, a killer comet, a global tsunami, or a super volcano, respectively.

Larry Hall’s Luxury Survival Condo is unique in that his bunkers are built inside repurposed missile silos built by the Army Corps of Engineers. In terms of design, they’re stunning. And two million dollars for a spot…before they sold out. Which leads to this interesting predicament noted by the article’s author:

So with all the comforts that any wealthy survivalist could throw money at, Larry Hall has designed the survival condo for likeminded millionaires savvy enough to realize that if or when the economy or society goes to pot, their cash-at-hand will be worthless, and their survival investment will be money well spent. But surely Hall realizes this, too? It’s my hope that, come time to batten down the hatches, those people sharing his oxygen don’t get on his nerves when all the profit he’s made becomes worthless in a barter-based economy.

Chinese Dig in for ‘approaching doomsday’ by Rita Alvarez Tudela

More architecture for the apocalypse. Imagine the end of the world actually happening, the only survivors being the guys brazen enough to lock themselves inside a giant ping-pong ball. Or better yet, imagine the end of the world being brought on by a global tsunami, earth turned into one giant ocean dotted with tsunami survival pods carrying the last surviving members of mankind, trapped inside giant ping-pong balls.